On This Page

In Brief

- Roses can be infected with diseases caused by fungi, bacteria, and viruses.

- Many rose diseases develop when roses receive too much water.

- Fungicides are available for home garden roses but must be applied as a preventive treatment.

- Disorders from nonliving causes include sunburn, nutrient deficiency, and herbicide damage.

Pest Notes: Introduction

A variety of plant pathogens (bacteria, fungi, and viruses) can attack roses and lead to diseases. The most common rose disease in California gardens and landscapes is powdery mildew, but other diseases including rust, black spot, botrytis, downy mildew, and anthracnose may cause problems where moist conditions prevail.

In addition to diseases caused by plant pathogens, roses may display damage symptoms resulting from chemical toxicities, mineral deficiencies, or environmental problems. Such problems are termed abiotic disorders and improving environmental conditions can often correct these symptoms.

This publication helps readers manage rose diseases and problems by offering an integrated approach which includes choosing varieties and irrigation practices carefully, promoting air circulation by pruning correctly and providing sufficient space between plants, and removing severely infested material promptly. Although some rose enthusiasts consider regular application of fungicides a necessary component of rose culture, many gardeners can grow plants with little to no use of fungicides, especially in California’s dry interior valleys.

Leaf and Shoot Diseases and Disorders

Fungal diseases

Powdery mildew, caused by the fungus Podosphaera (previously Sphaerotheca) pannosa var. rosae, produces white-to-gray powdery growth on both sides of leaves, as well as shoots, sepals, buds, and occasionally on petals. Leaves may distort and drop.

Powdery mildew does not require free water on plant surfaces to develop and can even infect roses during California’s warm, dry summers. Overhead sprinkling, such as irrigation or washing, during midday may limit the disease by disrupting the daily spore-release cycle, yet allows time for foliage to dry before evening.

The pathogen requires living tissue to survive, so pruning, collecting, and disposing of leaves during the dormant season can limit infestations. However, these sanitation practices may not entirely eradicate powdery mildew since airborne spores from other locations can provide fresh inoculum.

Rose varieties vary greatly in resistance to powdery mildew, with landscape (shrub) varieties among the most resistant. Glossy-foliaged varieties of hybrid teas and grandifloras often have good resistance to powdery mildew as well. Plants grown in sunny locations with good air circulation are less likely to have serious powdery mildew problems.

Fungicides may be available, but generally you must apply them to prevent rather than eradicate infections, so timing is critical and repeat applications may be necessary. In addition to synthetic fungicides, other materials having fungicidal properties are available, including horticultural oils, neem oil, sulfur, potassium bicarbonate, and the biological fungicide Bacillus subtilis. Except for the oils, these fungicides are primarily preventive, although potassium bicarbonate has some eradicant activity. Oils work best as eradicants but also have some protectant activity. Do not apply oils to water-stressed plants or within two weeks of a sulfur spray.

See the Pest Notes: Powdery Mildew on Ornamentals for more details on management.

Downy mildew, caused by the oomycete Peronospora sparsa, requires a narrow range of temperature and humidity to thrive. Angular purple, red, or brown spots appear between veins on leaves, which then become yellow and drop. Sometimes, downy mildew may produce pale, felty patches of fruiting bodies on the undersides of leaves, helping to distinguish it from powdery mildew, which typically produces visible mycelial growth on both sides of leaves, as well as shoots and buds. Because downy mildew requires moist, humid conditions, it is most likely to cause problems in coastal areas of California and, during a narrow period of time in spring and fall, in the Central Valley.

To reduce downy mildew, increase air circulation through pruning and avoid frequent overhead irrigation that results in prolonged periods of wet foliage. Downy mildew spores can survive on fallen leaves for weeks when humidity is high and temperatures are mild, so sanitation is essential if these conditions are present. These spores become dormant at relative humidity levels below about 80%, and are killed when exposed to temperatures greater than 85°F for several days. Control with fungicides is very difficult. Environmental management is much more likely to be effective.

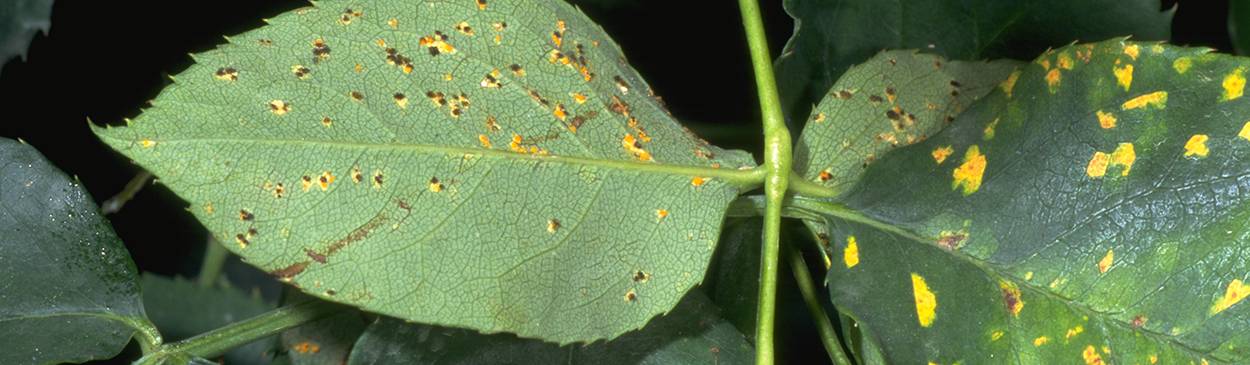

Rust, caused by the fungus Phragmidium mucronatum (formerly P. disciflorum), prefers cool, moist weather such as that found in coastal areas of California but may also be a problem inland during wet years. Infected leaves may drop prematurely, and exhibit small, orange pustules on the undersides, while the upper sides often discolor.

Avoid overhead watering and prune back severely affected canes. During the winter, collect and dispose of any leaves remaining on the plants and those that have fallen off. Plants can tolerate low levels of damage without significant losses. You can use preventive applications of fungicides, but attempting to keep plants rust-free may require frequent applications, which may not be justifiable in garden or landscape situations.

Black spot, caused by the fungus Diplocarpon rosae, produces black spots with feathery or fibrous margins on the upper surfaces of leaves and stems. Small, black fruiting bodies are often present in spots on the upper sides of leaves. No fungal growth occurs on the undersides.

This fungus requires free water to reproduce and grows when leaves remain wet for more than seven hours. If washing plants, for example to reduce aphid numbers, do it in the morning or midday, so leaves have a chance to dry before evening. Provide good air circulation around plants. Remove fallen leaves and other infested material, and prune out infected stems during the dormant season.

Black spot is usually not a problem in the interior of California, but may be present in humid, coastal areas. In general, miniature roses are more susceptible than other types, although a few varieties are reliably resistant to all strains of black spot. Oils, including neem oil, or other fungicides such as potassium bicarbonate and sulfur, have been shown to be effective in reducing black spot. If cultural controls prove to be inadequate, fungicides such as chlorothalonil may be preventative options for the next season.

Anthracnose, caused by the fungus Elsinoe rosarum (formerly Sphaceloma rosarum), results in leaf spots. When first formed, spots are red or sometimes brown to purple. Later the centers turn gray or white and have a dark red margin. Fruiting bodies may appear in the middle of the spot, and the lesion may fall out, creating a shot-hole appearance.

Rose anthracnose spreads during extended wet weather when temperatures are moderate. Because these conditions are infrequent in California, it is not a common problem. However, it can be an issue where sprinkler irrigation is routine, so the use of soaker hoses or drip systems may prevent this disease. Sanitation and adequate spacing between plants also limit disease development. Hybrid teas and old-fashioned climbing and rambler roses are the most affected.

Viral diseases

Viruses and virus-like diseases occur wherever roses grow. For home gardeners, the problem is most often one of unsightly foliage, with possible decreased plant vigor and flowers that are smaller, fewer, or both. These viruses are most commonly spread during propagation through budding an infected scion onto a healthy rootstock or a healthy scion to an infected rootstock. Disease symptoms are not always obvious, which is why the use of virus-tested planting stock is advantageous. Pruning tools cannot spread rose viruses.

Rose mosaic disease (RMD) is common wherever roses are grown and is named after the leaf symptoms. Ringspots, line patterns, mosaics, and distortion or puckering are typical. Leaf symptoms will vary depending on which virus or viruses are present, the rose cultivar, the time of year, and growing conditions. Visual symptoms also can be transient; for example, hot, bright days can cause the symptoms to appear milder or disappear. However, the virus remains, and the plant becomes a symptomless carrier.

In the United States, RMD is the result of an infection with Prunus necrotic ringspot virus, Apple mosaic virus, or both. In other countries, Arabis mosaic virus also contributes to RMD. These viruses may be present alone or in combination, accounting in part for the array of symptoms observed on infected plants. An accurate diagnosis may require laboratory tests. As with many viruses, transmission occurs when virus-infected plant material is grafted onto healthy plant material. Experimental evidence indicates rose mosaic can spread via root grafts. RMD is controlled by removing infected plants and using virus-tested propagative material.

Rose rosette disease (RRD) is a very destructive disease of roses east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States. Symptoms include excessive lateral shoot growth and thorniness, witches’ broom, leaf proliferation and malformation, mosaic, red pigmentation, and eventually death. Rose rosette disease was positively identified in two locations in Kern County, California, in 2018.

RRD was first described in the 1940s, but the viral pathogen rose rosette virus was only recently identified. The virus has long been known to be transmitted by the eriophyid mite, Phyllocoptes fructiphilus. Multiflora rose, an invasive species in many areas, is highly susceptible to RRD and may serve as a source of inoculum.

Plants suspected of RRD should be removed, including roots, and destroyed. Effective control of eriophyid mites can reduce the risk of spread, but is very difficult and impractical in most gardens and landscapes. Using clean plants is the best method of preventing the disease.

Rose spring dwarf disease (RSD) has been found in California and other parts of the United States. RSD causes rosetting or a balled appearance in the new growth following budbreak. The leaves first emerging in the spring are recurved or very short and show conspicuous vein clearing or a netted appearance. These symptoms become less apparent as shoots eventually elongate. Canes may develop a zigzag pattern of growth as the season progresses.

RSD is caused by infection with the virus Rose spring dwarf-associated virus. Transmission studies have identified rose-grass aphid and yellow rose aphid as vectors for this virus, which has a wide host range.

RSD is controlled by removing infected plants and using virus-tested propagative material.

Other viruses, such as Rose yellow vein virus, Rosa rugose leaf distortion virus, and Rose yellow mosaic virus, have been recently identified as a result of advances in diagnostic technologies. These viruses, in addition to previously identified viruses such as Blackberry chlorotic ringspot virus, Tobacco streak virus, Strawberry latent ringspot virus, Tomato ringspot virus, and Tobacco ringspot virus present problems to commercial rose growers. Rose gardeners, retailers, and regulatory officials don’t like the look of the symptoms. Cut flower producers may see a significant decrease in production, bloom quality, or both, depending on the variety of rose and type of virus. Nursery plant producers may face rejection of interstate shipments.

Using clean planting stock is the best management practice to limit viruses in roses. Plant material that has been tested for and found free of viruses known to cause disease symptoms is referred to as clean stock. For the home rose grower, no effective method exists for eliminating rose viruses. Use of virus-indexed stock—plants that have tested negative for these viruses by laboratory and field methods—for field propagation is the recommended preventative practice for commercial producers.

Flower Petal and Bud Diseases and Disorders

Botrytis blight, caused by the fungus Botrytis cinerea, thrives under conditions of high humidity and cool temperatures. Affected plants have spotted flower petals and buds that fail to open, often with woolly, gray fungal spores on decaying tissue. Twigs die back, and large, diffuse, target-like splotches may form on canes.

Decrease the humidity around plants by modifying irrigation and pruning techniques and reducing ground cover. Remove and dispose of fallen leaves and petals and prune out infested canes, buds, and flowers. Botrytis blight is a problem usually only during spring and fall in most of California and during summer along coastal areas when the climate is cool and foggy.

Rose phyllody is a flower abnormality recognized for more than 200 years in which leaf-like structures replace flower organs. The fundamental cause seems to be changes in plant hormone balance, brought about by abiotic conditions such as environmental stress, or by living infectious agents. Some rose varieties such as floribundas are more likely to exhibit phyllody symptoms, probably due to genetic susceptibility. In fact, one floribunda ancestor is Rosa chinensis, from which came the “Green Rose,” a curious variety that has a stable mutation causing phyllody in all its flowers.

Phytoplasmas and viruses can disrupt normal hormone production, inducing phyllody in many plant species, but play less important roles in rose phyllody. Although a few reports exist of rose phyllody caused by phytoplasmas, the association is poorly documented. Insects—most often leafhoppers—can spread these pathogens, so the appearance of phyllody often raises concerns about possible disease spread through the garden.

In roses, the most common cause of phyllody is environmental stress, such as hot weather when flower buds are forming, or water stress. If environmental factors are the cause, affected plants usually have normal and abnormal flowers simultaneously but otherwise look healthy. When the weather cools, the bush resumes producing only normal flowers.

Rose growers familiar with the characteristics of individual varieties can assess if phyllody is caused by disease or environmental stress by carefully examining plants. A lack of stunting or yellowing and good overall growth indicate a virus or phytoplasma is not likely the cause, but instead an individual flower is responding to specific environmental conditionals. No management practices are suggested other than pruning out individual blooms.

Cane Diseases and Disorders

Botrytis blight, as described above, can cause twig dieback and large, diffuse, target-like blotches on canes.

Winter injury from cold temperatures results in dead or dying flowers, twigs, and stems. A thick layer of leaf mulch may protect roses during the winter in cold mountain areas. Stem canker diseases caused by pathogens that move into injured tissue may follow winter injury. It is important to provide proper care to keep plants vigorous to prevent problems. Prune out diseased or dead tissue, making cuts at an angle in healthy tissue just above a node, and avoid wounding canes. Cankers often develop after cold temperature injury, so early spring pruning may not effectively eliminate them if late frosts occur. Additional late spring pruning may be necessary.

Sunburn appears as blackened areas, especially on the south and west sides of canes. Excessive heat from the sun or reflected heat from masonry, vinyl siding, or rock mulch on rose canes causes sunburn. Often, sunburn occurs as an indirect result of drought stress or spider mite pressure leading to defoliation.

Crown gall, caused by the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens, affects many woody plants including fruit trees, ornamentals, and roses as well as some herbaceous plants including chrysanthemums and daisies. Crown gall bacteria invade plant tissue after wounding. Galls, in the form of large, distorted tissue growth, can form at the base of the cane, on roots, or farther up on stems. Infected canes can be stunted and discolored. Do not plant susceptible plants in infested soil or near infected plants. Do not accept rose plants dug from someone’s yard that have crown gall symptoms. Purchase and plant only high-quality stock.

Abiotic Disorders

Nutrient deficiencies cause various symptoms such as interveinal chlorosis (yellowing), vein yellowing, tip and marginal necrosis, and premature leaf drop. Many California soils have low percentages of organic matter and the nitrogen reserve is typically low, so nitrogen must be added as organic or inorganic fertilizer.

Micronutrient deficiencies, especially iron and zinc, appear as interveinal chlorosis of new leaves. These elements may be deficient because soils are too wet or too alkaline, or because the soil type, such as sandy loam, is low in micronutrient content. Because inorganic forms of iron and zinc form insoluble precipitates in alkaline soils, you can apply iron and zinc directly to foliage. You can apply iron and zinc in a chelated form to either soil or foliage.

Nutrient excesses may limit rose growth if the total salt level becomes too high. A value of less than or equal to 2 dS/m (decisiemens per meter) is recommended. At a higher concentration of total salts, plants may show a lack of vigor and short shoots, although no definitive leaf symptoms may appear. If salt concentrations are found to be greater than 4 dS/m, you also may see browning of the leaves.

A few nutrients cause specific toxicities. Boron, which is found at high levels in some California soils, will cause stunting of plants, chlorosis, and marginal browning of the newest leaves. A soil concentration of less than or equal to 1 part per million is recommended. To remediate a problem with high boron, soil must be leached. That is, good quality water (low in boron) is applied and moves down through the soil profile, dissolving boron and carrying it below the root zone.

Herbicide damage may manifest itself in a variety of symptoms, which include cupped, curled, or yellowed leaves, small leaves, or death of the entire plant. The herbicide class and dosage to the plant determine which symptoms appear and their severity. Injury from glyphosate (e.g., Roundup) is relatively common.

Damage symptoms from glyphosate may not appear during the application season, especially if the application occurred in autumn, but may appear the following spring as a proliferation of small shoots and leaves. The plant will outgrow the injury if the dosage was not too high.

References

Al Rwahnih M, Karlik J, Diaz-Lara A, Ong K, Mollov D, Haviland D, Golino D. 2019. First Report of Rose Rosette Virus Associated with Rose Rosette Disease Affecting Roses in California. Plant Disease 103: 380.

Dreistadt SH, Clark JK, Martin TL, Flint ML. 2016. Pests of Landscape Trees and Shrubs: An Integrated Pest Management Guide, 3rd Edition. UC ANR Publication 3359. Oakland, CA.

Elmore CL, Stapleton JJ, Bell CE, DeVay J. 1997. Soil Solarization: A Nonpesticidal Method for Controlling Diseases, Nematodes, and Weeds. UC ANR Publication 21377. Oakland, CA.

Flint ML, Karlik JF. 2019. Pest Notes: Roses: Insects and Mites. UC ANR Publication 7466. Oakland, CA.

Horst RK. 1983. Compendium of Rose Diseases. St. Paul: APS Press.

Karlik JF. 2019. Pest Notes: Roses Cultural Practices and Weed Control. UC ANR Publication 7465. Oakland, CA.

Laney AG, Keller KE, Martin RR, Tzanetakis IE. 2011. A discovery 70 years in the making: characterization of the rose rosette virus. Journal of General Virology 92(7): 1727-1732.

Pemberton HB, Ong K, Windham M, Olson J, Byrne DH. 2018. What is rose rosette disease? HortScience 53(5):592-595.

Salem N, Golino D, Falk B, Rowhani, A. 2008. Identification and partial characterization of a new luteovirus associated with rose spring dwarf disease. Plant Disease 92: 508-512.

Resources