In Brief

- Squash bugs are a common pest in vegetable gardens, targeting cucurbits such as pumpkin, squash, and melon.

- They feed on plant foliage which results in plant wilt, and in some cases, plant death.

- Adult squash bugs are small, winged, and grayish brown with a flat back. The edges of the abdomen and underside of the insect have orange to orange-brown stripes.

- Prevent squash bug infestations by removing old cucurbit plants after harvest and keeping the garden free from rubbish and debris that can provide overwintering sites for squash bugs.

Pest Notes: Introduction

The squash bug, Anasa tristis (order Hemiptera), is a common pest in vegetable gardens. There are multiple species of squash bugs, but A. tristis is the most common one. They feed on plant foliage and fruit using straw-like mouthparts to pierce the surface and suck plant sap. Feeding by squash bugs can cause plants to wilt or die and can cause fruit to rot. Squash bugs target vegetable crops in the cucurbit family, such as pumpkin, squash, and melon, and can be especially aggravating to gardeners when populations reach large numbers.

Identification and Biology

Squash bugs are 5/8 inch long and one third as wide. Adults are winged and grayish brown with a flat back. The edges of the abdomen and underside of the insect have orange to orange-brown stripes. If necessary, turn squash bugs over to better identify them.

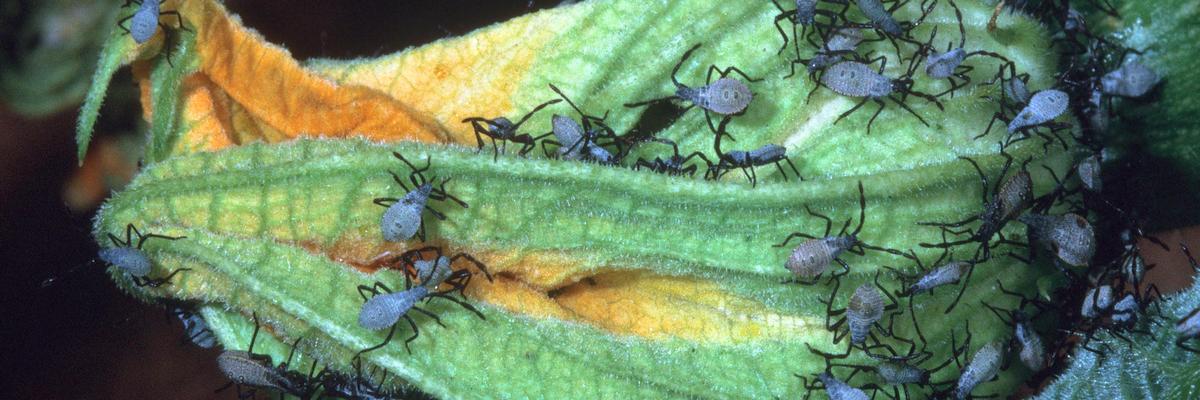

Squash bug eggs are 1/16 inch long and laid in groups or clusters. Eggs are bronze to brick red and are usually found in groups of 15 to 40 on the undersides of leaves or stems in the spring and summer. Nymphs (immature stage) hatch 1 to 2 weeks later and are wingless, spiderlike, and often covered with a whitish powder. Nymph size varies between 3/16 to 1/2 inch and range in color from mottled white to greenish gray and have black legs. Nymphs later turn dark brown and begin to resemble adults, growing wing pads in their later stages. After molting several times into increasingly larger nymphs (instars), they become adults. This process takes 4 to 6 weeks. Various life stages of the squash bug population can overlap and all of them can be found at a given time during the growing season.

Squash bugs feed on garden crops of summer and winter squash as well as pumpkin. Both adults and nymphs can be found near the crown of the plant, underneath leaves or under dirt clods, fruit, or other protective cover. When disturbed, they disperse quickly.

Squash bug adults find shelter in the fall under dead leaves, rocks, wood, and other garden debris and rest in these places throughout the winter (overwintering). Once spring approaches, they fly from their protective habitats to nearby cucurbit plants where they feed, mate, and lay eggs. Eggs hatch in 5 to 10 days. Adults and nymphs feed on the plants. They complete their life cycle in 6 to 8 weeks. Squash bugs may have 2 to 3 generations per year in California. The second or third generation adults overwinter and produce eggs the following spring.

Often, squash bugs, stink bugs, and other large true bugs are mistaken for each other. Squash bugs and stink bugs are similar in shape, and both have disagreeable odors when crushed or disturbed. Generally, stink bugs are wider and rounder than squash bugs. In the garden, stink bugs are not considered pests of cucurbits and prefer to feed on flowers and fruits of other plants, such as tomatoes and legumes. Other bugs that can be confused with the squash bugs include bordered plant bugs, boxelder bugs, leaffooted plant bugs, and the invasive brown marmorated stink bug.

Damage

Injury by squash bugs is limited to squash, pumpkin, melon, and other plants in the cucurbit family. Adults and nymphs cause damage by sucking plant juices. Leaves lose nutrients and water and become speckled, later turning yellow to brown. Heavy bug feeding interrupts the flow of water and nutrients in the xylem and plants begin to collapse and wilt, and the point of attack becomes black and brittle. This symptom is also called “Anasa wilt.”

Small plants can be killed completely, while larger cucurbits begin to lose runners. The wilting resembles bacterial wilt, which is a disease spread by another pest of squash, the cucumber beetle. Wilting caused by squash bugs, however, is due to feeding and not a true disease. Additionally, overwintering squash bugs can harbor and transmit a bacterium, the causal agent of cucurbit yellow vine disease, when they feed on the plant’s sap. This disease has been observed to inflict high crop losses, especially on watermelon, pumpkin, cantaloupe, and squash. The disease has been reported in the Midwest and Eastern states, but its prevalence in California is not well known.

During the summer, squash bugs routinely feed from sheltered areas on the undersides of fruit. This can cause young fruit to abort or become misshapen, and can cause scarring on the surface of the fruit as it expands. Feeding wounds on the underside of the fruit, in combination with warm weather and high humidity from irrigation, can allow for the entry of opportunistic pathogens. This causes the undersides of pumpkins, gourds, and other fruit that sit on the ground to rot or decay while on the vine or shortly after harvest.

Management

In spring, search for squash bugs hidden under debris, near buildings and in perennial plants in the garden. Inspect young plants daily for signs of wilting or the presence of egg masses and mating adults, then destroy any squash bugs found.

Cultural Practices

Cultural controls are practices that reduce pest establishment, reproduction, dispersal, and survival. The best cultural strategy for squash bug control is prevention through sanitation. Remove old cucurbit plants after harvest. Keep the garden free from rubbish and debris that can provide overwintering sites for squash bugs. At the end of the gardening season, compost all vegetation or thoroughly till it under. Place wooden boards throughout the garden and check under them every morning and handpick or vacuum any bugs found under the wooden boards. During the growing season, pick off and destroy egg masses as soon as you see them. Use protective covers such as plant cages or row covers in gardens where squash bugs have been a problem in the past and remove covers at bloom to allow for pollination. As fruit on the ground gain size, periodically roll them over and smash any bugs that are found. Placing fruit like pumpkins on a small pedestal that raises them off the ground can reduce squash bug feeding and help prevent rot on the undersides of fruit.

Trellising

Growing vining types of squash and melons on a trellis can make them less vulnerable to squash bug infestation compared to the bush types. This is because squash bugs prefer to hide under the thick foliage of the bushes, and also prefer to laying eggs and feed close to the ground.

Resistant Varieties

Some squash varieties, including Butternut, Royal Acorn, and Sweet Cheese, are more resistant to squash bugs. Sturdy and bigger plants can tolerate a higher level of damage compared to the young and weaker plants which may die due to feeding.

Biological Control

Squash bug eggs, nymphs and adults are fed upon by multiple predators such as spiders, ground beetles, big-eyed bugs, and various types of lady beetles (ladybugs) , all of which contribute to reducing squash bug population. The parasitic tachinid fly, Trichopoda pennipes, which lays its eggs on squash bugs, has been introduced into California and may be found in some gardens. Look for the eggs of this parasite on the undersides of squash bugs.

Chemical Control

Squash bugs are difficult to kill using insecticides because egg masses, nymphs, and bugs are often hidden near the crown of the plant and difficult to reach with sprays. Several insecticides are available that are less toxic to the environment including products containing insecticidal soaps and oils such as Insect Killing Soap Concentrate II (e.g., Safer® Insect Killing Soap) and Clarified Hydrophobic Extract of Neem Oil (e.g. Ferti-lome® Neem). However, these active ingredients are only effective against the smallest stages of nymphs, and good penetration into the plant canopy must be achieved with the insecticide applications to ensure that nymphs under the leaves and deep within plants will be covered. Other more toxic pesticides are also registered for use on squash bugs; however, these materials should be used with caution since they can harm the bees that are required for squash pollination as well as other beneficial insects, such as the predators and parasites that help control other pest insects and mites. In addition, they are not likely to give better control than handpicking combined with softer chemicals. Additional insecticides that are available in California and that may be effective against squash bugs include azadirachtin (e.g., Aza-Direct), azadirachtin mixed with oils (e.g., Debug Turbo) or pyrethrins (e.g., Azera), spinosad (e.g., Monterey Garden Insect Spray), and pyrethrins (e.g., Monterey Bug Buster-O).

References

Cranshaw W. 1998. Pests of the West. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Edelson J, Simons B, Hillock, D. 2016. Home Vegetable Garden Insect Pest Control. OK State Univ. Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet EPP-7313.

Flint ML. 2018. Pests of the Garden and Small Farm: A Grower’s Guide to Using Less Pesticide, 3rd Edition. UC ANR Publication 3332. Oakland, CA.

Burkness EC, Hutchinson WD. Squash Bug. Univ. of Minn., Dept. Entomology.

HB Doughty, Wilson JM, Schultz PB, Kuhar TP. 2016. Squash Bug (Hemiptera: Coreidae): Biology and Management in Cucurbitaceous Crops, Journal of Integrated Pest Management, Volume 7, Issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmv024

Resources

- About Pest Notes

- Glossary

- Compare Risks from Pesticides Mentioned

- WARNING ON THE USE OF PESTICIDES

- List of other Pest Notes